Cocopeat vs. Coco Chips| Physical Properties, Use Cases, and Pros and Cons

Cocopeat vs. Coco Chips | Uses & Key Differences

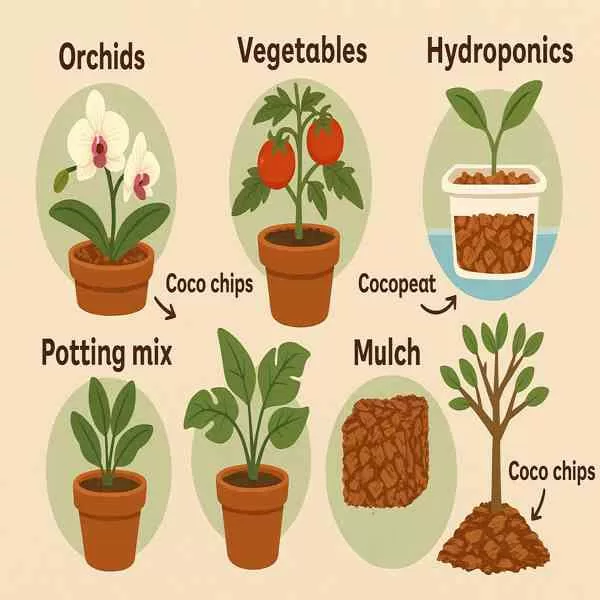

Cocopeat (also called coir pith) and coco chips are both growing media derived from the coconut husk, but they differ markedly in form and use. Cocopeat is the fine, spongy coir dust left after extracting long fibers – it has a powdery texture similar to peat moss. In contrast, coco chips are small chunky pieces of the husk, created by cutting or grinding the fibrous husk into coarse granules. Both products are 100% organic and sustainable, and they share benefits like improving soil structure and water holding while being more eco-friendly than peat moss. However, coco chips and cocopeat differ in texture, suitability for different plants, and how they perform in commercial growing setups. Below is a detailed comparison of cocopeat and coco husk chips across key parameters.

Physical and Chemical Differences Between Coco Chips and Cocopeat

Structure & Texture: Cocopeat consists of very fine particles of coir (coir dust) and feels soft and soil-like, with a dark brown color. Coco chips are much coarser – usually 1–2 cm fibrous chunks – brown in color with visible fiber bits. The chip form creates large air pockets, whereas the fine peat packs more tightly. Coco chips essentially combine properties of coir fiber and pith: they retain some moisture while providing plenty of air space. By contrast, cocopeat’s fine granules can hold water like a sponge but have less inherent air porosity unless mixed with coarse material.

Water Retention and Drainage: Cocopeat is excellent at holding moisture — it can absorb and retain about 6 to 8 times its dry weight in water, while still allowing good drainage and airflow to roots. This makes it excellent for moisture-loving plants or reducing watering frequency. Coco chips hold water too, but only a moderate amount – their larger particle size means excess water drains quickly, leaving air in pore spaces. In practical terms, cocopeat can retain much more water than chips, while chips provide superior drainage and aeration to prevent waterlogging. For example, fine coir dust can hold ~855 ml of water per liter (for particles <0.125 mm), whereas coarse chunks (>2 mm) hold only ~165 ml per liter. Thus, cocopeat keeps media moist longer, whereas coco chips dry out faster but help “breathe” by maintaining air pockets.

Aeration and Structure: The fibrous structure of husk chips means they resist compaction and create an open, airy medium. Even when wet, coco chips maintain structural integrity, preventing the media from collapsing. Cocopeat’s fine particles can settle and compact slightly over time, especially if used alone, which reduces air space. That said, quality cocopeat is noted for not shrinking excessively or collapsing upon re-wetting (unlike peat moss). Still, a mix of particle sizes is often optimal – research finds that combining fine coir with some coarser particles yields the best balance of water and air. In summary, chips offer exceptional aeration, while peat offers greater moisture retention, and blends can harness both qualities.

pH Levels: Both cocopeat and coco chips are naturally near-neutral to slightly acidic in pH, favorable for most plants. Cocopeat tends to be a bit more acidic (around pH 5.5–6.5), while coco husk fibers/chips are often closer to neutral (pH 6.0–6.8). For instance, one source notes coir pith typically falls around pH 5.9 (median), whereas coarser coir is often 6+. In either case, this pH is far less acidic than sphagnum peat moss (which is ~pH 3.5–4.5), meaning coconut coir products usually don’t require liming. The neutral-to-slightly acidic pH of both chips and peat makes them immediately plant-ready in most scenarios.

Salinity (EC) and Nutrients: A critical chemical difference lies in electrical conductivity (EC) and salt content. Coir naturally contains potassium, sodium, and chloride salts – especially if the husks were soaked in saltwater during processing. Unwashed cocopeat (high EC) can have EC >0.8 mS/cm and very high K/Na/Cl levels, which can impede plant growth. Quality horticultural cocopeat is usually “low EC” (<0.5 mS/cm) after thorough washing, making it suitable even for salt-sensitive crops. The same principle applies to coco chips: they should be washed to leach excess salts (for example, orchid-grade husk chips are pre-washed to protect roots). Fine cocopeat tends to hold more salts initially than coarse chips (small particles have more surface area for salts), so rinsing is vital. In terms of inherent nutrients, coir products are low in immediately available nutrients. Cocopeat contains small amounts of N, P, K (often higher K content) but not enough to fully feed plants. Coco chips similarly are more or less inert and need fertilization. One minor difference is that cocopeat may carry marginally more potassium and micronutrients than chips, simply because the pith has cation exchange sites and often retains nutrients from the coconut pulp. Meanwhile, coco fibers/chips have been noted to contain natural rooting hormones and stimulants, despite their low nutrient value. In practice, growers treat both as soilless media that require added nutrients, but note that cocopeat releases a flush of potassium and may tie up some calcium and magnesium, so nutrient programs are adjusted accordingly.

Summary: In sum, cocopeat is fine-textured, with high water retention and slight acidity, whereas coco chips are coarse, well-aerated, and nearly neutral in pH. Cocopeat holds more moisture and nutrients (and potentially more residual salts if unwashed), while coco chips provide superior drainage and physical stability. These differences make each form preferable for certain plants and systems, as detailed next.

Note- Many professional growers, manufacturers and coir pith exporters—including top cocopeat suppliers in Tamil Nadu—recommend using washed, low-EC cocopeat for optimal plant health. especially in commercial and hydroponic setups.

Cocopeat vs. Coco Chips| Suitability for Various Plants and Grow Systems

Different plant types and cultivation systems benefit from specific properties of cocopeat vs. coco chips. Below we address which form is better suited for various uses:

- Orchids and Epiphytic Plants: Epiphytic orchids (like Phalaenopsis) thrive in a chunky, well-draining medium, since their roots expect lots of air and quick drying cycles. Coco husk chips are ideal here – they function much like orchid bark, but with added moisture retention. Coco chips hold more moisture than fir bark while still keeping roots aerated, creating a humid micro-environment without waterlogging the orchid roots. Growers often mix coco chips with coarse perlite or charcoal for orchids, or use chips as a supplement to bark mixes. Cocopeat (fine coir) is generally unsuitable as a primary orchid medium because it stays too wet and could suffocate orchid roots. However, a small amount of cocopeat or moss might be mixed in for moisture in certain cases. Overall, coco chips (or fiber chunks) are the preferred coir product for orchids, bromeliads, and other epiphytes that demand excellent drainage and airflow.

- Vegetables and Fruit Crops: Many vegetables, especially in container or hydroponic culture, respond well to cocopeat’s water-retentive properties. Cocopeat is widely used for crops like tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, strawberries, and leafy greens, often in the form of grow bags or blocks. Its ability to hold moisture and nutrients around the root zone supports heavy-feeding veggies. For example, greenhouse tomatoes and berries are commonly grown in bags filled with coco coir pith, yielding great results in terms of growth and yield. Coco chips are less commonly used alone for small herb or vegetable plants, but they can be blended with cocopeat or used in coarse grades for specific needs. In situations where extra drainage is needed (e.g. for herbs that prefer drier roots or for aloe/vermicompost bins), adding some husk chips can improve air space. Notably, salt-sensitive vegetables (lettuce, spinach, strawberries) require low-EC coir – washed cocopeat is crucial for these, whereas unwashed coir would harm them. In summary, most vegetables favor cocopeat for its soil-like consistency and moisture, possibly with some chips or perlite mixed in to optimize the air–water balance.

- Hydroponic Systems: In hydroponics, cocopeat has become a standard soilless medium, often replacing peat moss or rockwool. It can be used in dutch buckets, troughs, or slabs to anchor plant roots while nutrient solution is fed. Cocopeat’s high water retention allows longer intervals between irrigation in drip systems and provides a buffer of nutrients. Coco chips, however, also have a niche in hydroponics. They are sometimes marketed as “coco croutons” – small cubes of coir husk – to be used in flood-and-drain (ebb/flood) tables, drip buckets, or net pots. The chips drain faster and hold more oxygen, which can be advantageous for certain hydro setups or crops prone to root rot. For instance, some indoor growers mix coco chips with coco dust to avoid over-saturation and improve root oxygenation. In an ebb-and-flow hydro system, coco chips can be used similarly to clay pebbles, and they reportedly keep roots happier by maintaining air pockets. The trade-off is that coarse coco chips will dry out faster between irrigations, so watering frequency must be higher compared to using cocopeat. In practice, commercial hydroponic farms (tomatoes, etc.) usually use a blend of coir grades: the finer pith to hold water and some fiber or chip to improve drainage. This yields a media that holds enough moisture but still flushes and re-wets easily. To summarize, both forms can work in hydroponics: cocopeat for maximum water-holding in drip systems, and coco chips or mixed grades for systems needing faster drainage and more oxygen to roots. In all cases, using low EC, properly buffered cocopeat is key to success in hydroponics to prevent salt buildup and nutrient lockout.

- Container Gardening and Potting Mixes: Cocopeat is highly suitable as a general potting soil ingredient. It is often used as a sustainable alternative to peat moss in potting mixes. Houseplants, ornamentals, and even shrubs/trees in containers can benefit from cocopeat mixed with compost, perlite, etc., as it improves moisture retention and soil structure. For instance, a simple potting mix recipe might include equal parts cocopeat, compost, and perlite, providing a balance of water and air. Coco chips in container mixes are used more selectively: they can be added to mixes for plants that need extra drainage (e.g. succulents, cacti) or placed at the bottom of large pots. A handful of coco chips at the bottom of a big container can help prevent the pot from drying out too quickly while still allowing good drainage. Certain aroid plants (monstera, pothos, philodendron) that enjoy chunky, well-aerated soil can also thrive with some coco husk chips mixed in, akin to using bark chips. In general, for small pots or seed starting, the fine texture of cocopeat is preferable (chips would be too coarse for seedling roots). For large containers and tropical plants, incorporating 20–30% coco chips into the medium can significantly boost aeration. Both cocopeat and chips are neutral and inert, so they can be combined with fertilizer blends to suit any plant.

- Summary: Cocopeat is a versatile base for potting mixes and container soils, whereas coco chips serve as an additive to increase drainage or as a primary medium for plants that demand chunkier soil structure.

- Mulching and Landscape Use: When it comes to using coconut coir as a surface mulch, coco husk chips are far more suitable than cocopeat. The chunky chips can be spread around garden beds, trees, or potted plants as an organic mulch layer. They help the soil stay moist, prevent weed growth, and gradually decompose to enrich the soil with organic matter. Unlike lighter mulches, coco chips tend not to blow away or scatter – they mat together slightly and stay put, even in wind or rain. This means you don’t need to reapply them as often as bark mulch, which can float off or degrade faster. In fact, coir chips are noted to be slow to decompose due to their high lignin content, giving a long-lasting mulch cover. Cocopeat, by contrast, is not typically used as a top mulch; the fine coir dust would likely blow away when dry and can form a crust when wet. That said, coir products do come in other mulch forms (e.g. coir fiber mats and blankets for erosion control), but these are fiber-based, not the peat dust. For home gardening, coco husk chips make an excellent mulch especially in tropical-themed gardens or around potted plants that need moisture retention. They also have an attractive natural brown appearance and a neutral pH that won’t acidify the soil. One consideration: in very dry climates, fine coco mulch or coir mats can help retain moisture better initially, but generally the chips suffice. In summary, for mulching purposes, choose coco chips for their water-holding, weed-suppressing, and stable qualities; cocopeat is better worked into soil than laid on top.

Best Choice for Commercial Use | Cocopeat or Coco Chips

Commercial Use | Durability, Cost & Reusability Compared

From a commercial grower or industry perspective, cocopeat and coco chips each have advantages and drawbacks:

- Durability and Longevity: Coco coir products are known for their slow decomposition. This is a pro in many contexts – they can be reused and don’t break down as fast as some organic media. Coco husk chips are particularly durable, thanks to high lignin content. In orchid cultivation, for example, premium husk chips last around 3 years in pot before needing replacement (whereas pine bark may decompose in 1–2 years). This durability means less frequent media replacement and thus labor savings in long-term crops. Cocopeat, being much finer, doesn’t “decompose” in the same way (it’s already a decomposed material), but over multiple crop cycles it can compact or lose structure slightly. Still, coir peat holds up well: it resists rot and can be used for several seasons if cared for. One con related to durability is that cocopeat can develop salt buildup or pathogen load over time, which may limit reuse (see Reusability below). Coco chips also can accumulate salts, but they are easier to wash out between uses due to high drainage. In landscape mulching, some consider coir chips less long-lasting than large bark chunks (as one supplier noted, very lightweight chips might break down or blow off faster than heavy wood chips). However, under most conditions coir’s rot-resistance is a plus.

- Bottom line: Both cocopeat and chips are quite durable media (with chips having an edge for multi-year use), reducing the need for frequent replacement in commercial operations.

- Cost Factors: The cost of cocopeat vs coco chips can vary depending on processing and region. Generally, raw coco coir is abundant and relatively low-cost, but processing (especially washing and grading) adds to price. In the global market, cocopeat is commonly sold in 5 kg compressed blocks and is competitively priced, making it a popular eco-friendly alternative to peat moss. Coco chips that are properly sized and washed for horticulture may be slightly more of a niche product and sometimes priced higher per volume than the common cocopeat blocks. For example, a greenhouse grower might pay a bit more for coco chip blocks or bags compared to standard cocopeat, because the chips are bulkier and fewer suppliers produce them at large scale. One industry observation is that peat moss remains a bit cheaper per cubic foot than coco coir in some markets – coir can cost about 1.5× the price of peat, partly due to shipping from tropical countries. However, the difference is shrinking as more growers and industries turn to coir-based products.

- Commercially, the grade of coir affects cost significantly: Low-EC, buffered cocopeat (hydroponic grade) is more expensive than high-EC, unwashed coir. The extra washing steps and quality control raise the price, but growers often must use the washed grade for sensitive crops. High-EC (unwashed) cocopeat or chips are cheaper and find use in applications like landscaping or salt-tolerant crops. Coco chips often come pre-washed (especially if marketed for orchids or hydroponics), so their cost inherently includes that processing. In bulk, both cocopeat and chips can be purchased in compressed bales, so freight is efficient – you’re shipping a dried, compacted product. One con on cost is if you are outside coconut-producing regions, you must import coir, so prices can fluctuate with global freight costs. On the pro side, many consider the environmental cost: peat’s environmental toll is high, so even if coir is slightly pricier, sustainability-minded businesses opt for coir. To summarize, cocopeat is often the more economical choice for large-scale growing (due to mass production and use), while coco chips might carry a premium if you need a specific washed, uniform product. Both are generally affordable in bulk, but price considerations include the grade (washed vs unwashed) and the distance shipped.

- Labor and Handling: Using coir products does come with some labor considerations. Both cocopeat and chips are typically sold in compressed bricks or bales that must be rehydrated before use. For a commercial operation, this means labor (and water) to expand the coir. The process is straightforward (soaking bricks in water for a few hours), but it needs to be planned in production schedules. Once expanded, coir is lightweight and easy to handle, which is a plus – workers find it less back-breaking than, say, lugging wet peat bales or heavy soil. Mechanization: Fine cocopeat can be run through automated pot-filling equipment and mixed with other components easily. Its consistency is like a loose peat, which flows well in machines. Coco chips, due to their chunkiness, might not feed as smoothly in automated systems designed for finer media. In automated transplanting or pot filling, large chips could cause bridging or require equipment adjustments. So for highly mechanized nurseries, pure cocopeat or a mix with smaller chips/fiber might be preferred to avoid jams. Potting and transplanting by hand is generally clean with coir – it is less dusty than peat (though coir does have some dust) and doesn’t stain hands as much. Another labor aspect is rinsing: if one buys high-EC coir to save cost, staff may need to wash or buffer it on-site to remove salts, which is extra labor. Checking the EC (Electrical Conductivity) is essential to make sure the cocopeat is safe and suitable for healthy plant growth. Many growers avoid this by buying pre-washed grades. Storage and transport on-site are also easy: compressed blocks take very little space and have virtually indefinite shelf life when dry, so nurseries can store coir compactly and hydrate as needed. Compared to bark or wood chips, which come in bulky bags or loose piles, coco chips compressed into blocks or compressed bags are more space-efficient to transport and stock. One con is that after hydration, coir materials swell to about 5–6 times their volume, so one must have sufficient mixing space or bins to handle the expanded medium. In hydroponic operations, using coco typically means handling and disposing of the used coir slabs or grow-bags after the crop – some labor needed to remove and possibly recycle or sterilize the coir. However, disposal is easier than rockwool (coir can be composted or spread on fields). Overall, coir is user-friendly but does require the step of hydration and possibly buffering. In terms of worker safety, coir is organic and generally safe, though the fine dust can be an irritant if it’s very dry – wearing a dust mask when breaking up dry bricks is advisable (a minor concern, similar to any potting mix). In summary, labor-wise, coir demands upfront preparation but then is easy to work with; cocopeat integrates well with automation, whereas large coco chips might entail more manual handling or specialized equipment adjustments.

- Reusability and Waste: A big advantage for commercial growers is that coco coir can be reused for multiple crop cycles under the right conditions. Manufacturers and growers often report that coir (peat or chips) can be reused 2–3 times before it starts to break down or show salt accumulation. For example, a tomato greenhouse might use coco slabs for two crop rotations, simply leaching and sterilizing (with steam or peroxide) between crops. Cocopeat’s structure actually improves after the first use in some cases – it becomes a bit more broken-in and still retains water well. However, by the third use, the fine particles may start to compact or the medium may harbor pathogens, so renewal is needed. Coco chips arguably have even better reusability because they are slower to break apart. An orchid nursery could potentially sterilize and reuse husk chips for several potting cycles, though in practice many will discard used media to avoid any disease spread. Still, coir’s reusability is a cost-saving and sustainability pro, compared to peat moss which is usually one-and-done. One con is that if a crop had disease (like root rot fungus), reusing the coir without proper sterilization could carry that over – but coir’s natural antifungal properties (high lignin and tannins) can suppress some pathogens, and proper sterilization mitigates this risk. After its useful life, coir waste is biodegradable and can be repurposed as a soil amendment or compost addition, which is a disposal advantage for commercial operations aiming for zero waste. In terms of durability affecting reuse: we noted that chips last longer; cocopeat fibers will eventually degrade. If coir is kept constantly wet (as in hydroponics), microbial action will slowly decompose it, so reused coir might have slightly less air capacity over time. But studies show coir degrades much slower than many organics – one source notes it can take decades to fully decompose in soil. As a result, even after use, spent coir can be used in landscaping. Summary: For commercial use, reusability is a strong pro for coir – with 2–3 uses possible, it lowers the effective cost per crop and generates less waste. This must be balanced with the need for proper treatment between uses (flushing, buffering nutrients, pasteurizing if needed).

In overview, commercial growers appreciate cocopeat for its consistency, availability, and ease of mixing, and value coco chips for specific crops (like orchids) or for improving drainage. The pros include sustainability, reusability, and plant health benefits (good root growth, no peat bog damage), while the cons can include slightly higher cost than traditional media, the need for initial processing (hydration), and ensuring quality control (salt content) for sensitive applications.

Hydroponics, Potting, and Mulch | Which Coco Medium Works Best

Comparing Coco Products in Hydroponics, Potting Mixes, and Mulching

Here we evaluate how cocopeat and coco chips perform in key horticultural applications, highlighting any differences in plant growth, maintenance, or outcomes:

- Performance in Hydroponics: Coco coir (especially cocopeat) has proven to be a high-performing hydroponic substrate. In practice, plants grown in cocopeat slabs often yield as well as those in rockwool, with the bonus of easier rewetting and reusability. The fine cocopeat holds moisture around roots but also drains excess solution quickly, preventing root anoxia. Growers note that coir doesn’t become hydrophobic upon drying like peat moss, so it rehydrates readily – a big performance plus in drip irrigation cycles. Coco chips, being coarser, tend to release water faster. This can be advantageous for avoiding oversaturation: for example, in an ebb-and-flow table, plants in coco chips get plenty of nutrition during floods but the media then drains and oxygenates the root zone thoroughly. The trade-off is the need for more frequent watering cycles to prevent the chips from drying too much between irrigations. In one informal trial, a grower using coco “croutons” (husk chunks) in a flood system found they had to flood every 4 hours for young plants, compared to longer intervals with finer coir. Once tuned, the plants grew very well in chips, developing extensive roots and showing no signs of overwatering. Nutrient management in coir is generally straightforward: because both peat and chips are inert, hydroponic growers can precisely control the nutrient solution. One caveat is that coir’s high potassium can cause initial calcium/magnesium uptake issues, so many hydro growers use a Cal-Mag supplement when using coco medium. Overall, both forms can deliver strong hydroponic performance when properly managed. Cocopeat might give slightly higher water availability, which can support maximal growth if fertigation is consistent. Coco chips offer more air and can reduce root diseases; in fact, some growers intentionally mix, say, 50% chips with 50% peat in hydroponic planters to get a balance of moisture and aeration. Ultimately, results have shown that coir quality (low salt, consistent gradation) is crucial – high-EC coir will harm hydro yields, whereas washed cocopeat significantly improves plant growth (e.g. One study showed that hydroponic tomato plants grown in thoroughly washed, low-EC cocopeat produced 25% higher yields compared to those grown in unwashed cocopeat.)

- . In summary, cocopeat excels in water retention for hydroponics, while coco chips improve oxygenation; using them appropriately (or in combination) leads to robust plant performance in soilless systems.

- Performance in Potting Mixes: As a component of potting soil, cocopeat has a well-established track record of improving moisture balance and plant health. Because it holds water without waterlogging, plants in mixes with cocopeat often show reduced drought stress. For example, adding coir to peat-based houseplant mixes can increase the time between waterings. Additionally, coir’s quick rewetting means that if a container does dry out completely, it is easier to water again (peat moss alone can become hard and resist wetting when bone dry). Cocopeat’s performance is also evident in root development: it promotes fibrous root growth thanks to its fluffy, well-aerated nature when mixed properly. Coco chips, when used in a mix, contribute to performance by preventing compaction over time. Fine potting soils can settle; mixing in some husk chips or larger coir pieces keeps the medium loose and well-draining. This is particularly beneficial for long-term container plantings (perennials, fruit trees in tubs, etc.) – the chips ensure that after months of watering, the soil has not collapsed into a dense mass. In terms of plant growth, species that demand excellent drainage (like many succulents, citrus, or palms) often perform better with some coarser media like coco chips added. The optimal performance often comes from using cocopeat and coco chips together. According to research by Abad et al. and others, using a blend of different coir particle sizes helps achieve the ideal balance between air flow and water retention in the growing medium. Fine particles hold nutrients and water, while coarse ones ensure air spaces – resulting in vigorous, well-rooted plants. Many commercial potting mixes now include coco coir (peat) as a base ingredient, and some specialty mixes (like certain orchid or bromeliad mixes) include husk chips.

- A practical example: a DIY mix for large planters might use 30% cocopeat, 20% coco husk chips, 30% compost, and 20% perlite. Such a mix would retain moisture moderately well but still drain quickly, supporting robust plant growth without daily watering.

- Nutrient considerations: Cocopeat has a high cation exchange capacity (CEC), which means it can hold onto nutrients (like ammonium, potassium) in the mix. This can be good (less leaching) but also means one must manage the fertilizer levels to avoid buildup. Husk chips have lower CEC, so nutrients flush out more freely; in a mix, chips can help avoid an overly nutrient-retentive situation. In practice, both media are nutritionally inert and need supplemental feeding, but they do not inherently provide much fertility aside from some K release from coir. Overall, plants in cocopeat-based potting mixes tend to show strong, steady growth with fewer watering issues, and mixes enhanced with coco chips resist compaction and overwatering problems.

Performance as Mulch: Using coco coir products as mulch has some distinct performance benefits. Coco husk chips, when applied as a 2–3 inch mulch layer, excel at conserving soil moisture – gardeners report that plants mulched with coco chips require noticeably less frequent watering. The chips act like little sponges: they absorb rainfall or irrigation, then slowly release moisture to the soil and reduce evaporation. Additionally, the weed suppression performance is comparable to other mulches; a thick layer of coir chips will block sunlight to weed seeds and form a physical barrier. One unique performance aspect is temperature moderation: the coir mulch insulates soil, keeping roots cooler on hot days and warmer on cool nights. This buffering can reduce plant stress in extreme weather. Another positive is that coco mulch is pest- and disease-free (being a processed product) and tends to discourage fungus gnats and other pests that might breed in continually moist soil, since the surface dries somewhat and contains tannins that pests dislike. Over time, the performance of coco chip mulch in improving soil is notable: as the chips very gradually break down, they add organic matter and improve soil structure underneath. Gardeners often find a loose, friable topsoil layer after long-term use of coco husk mulch. Compared to wood bark mulch, coco chips may break down a bit faster (depending on climate), but they also don’t tie up nitrogen as heavily – wood mulches can temporarily steal nitrogen from soil as they decompose, whereas coir’s high lignin slows decomposition and its carbon:nitrogen ratio is not as extreme, so it is relatively soil-friendly. Cocopeat is rarely used alone as mulch, but in some cases finely milled coir (coir fiber dust) has been used as a thin mulch or soil topper to prevent seedling desiccation. It can reduce evaporation in the short term, but it’s prone to being displaced by wind or crusting when dry, so it’s not as effective on its own.

Thus, in terms of mulch performance, coco husk chips outshine cocopeat, providing long-lasting moisture retention and protection for soil. An added convenience: when the season is over, the spent coir chips can be turned into the soil as a conditioner or reused, since they decompose slowly and improve soil tilth. Gardeners and even landscapers are increasingly exploring coco husk mulch, especially in areas where conventional bark mulch is scarce or where a neutral pH mulch is desired (coir mulch won’t acidify soil like pine bark can). The only potential downside performance-wise is cost (addressed below) and the light weight of dry chips until they settle – initial watering-in is needed to keep them in place. All considered, coir chips deliver excellent results as a moisture-conserving, stable, and attractive mulch layer.

Bulk Pricing & Sourcing Guide| Coco Chips vs. Cocopeat

Price and Sourcing (Bulk Availability, Transport, Shelf Life)

Bulk Availability: Cocopeat and coco husk chips are globally available through a network of suppliers in coconut-producing countries (India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Philippines, etc.). Coir products have become a commodity in horticulture; large 5 kg compressed blocks of cocopeat (yielding ~60–75 L of expanded media) are sold by numerous companies, and coco chips can be purchased in bulk blocks or bags as well. Many producers offer different grades (fine, medium, coarse chips) to suit client needs. Bulk buyers (like commercial greenhouses or soil companies) often import coir by the container-load. Cocopeat is more commonly traded in huge quantities, but coco chips are also available in bulk, especially for orchid growers, hydroponic farms, and landscapers who use them for mulch. The coir industry has established standards and classifications for export quality – for instance, the Coconut Development Board of India and others ensure products meet certain moisture and EC specs. In summary, both cocopeat and chips are readily sourced in bulk, though cocopeat is sometimes easier to find from multiple vendors, whereas high-quality uniform husk chips might come from specialized processors.

Ease of Transport: One reason coir has gained popularity is the efficiency of transport. Both cocopeat and coco chips are shipped in highly compressed form, drastically reducing volume. A dry coir brick can expand to 5–6 times its size when watered, so freight costs per unit of media are low. For example, a single pallet can hold hundreds of kilos of coir blocks, which expand to several cubic meters of growing media on site. This compression gives coir a big advantage over bulky bales of peat or wood chips. The lighter weight (when dry) also helps – coir fiber has low bulk density (as low as 0.06 g/cm³ in some cases). Coco chips, because of their chunk shape, don’t compress quite as tightly as the powdery peat, but they are still often compressed into 5 kg bricks or into bales. Manufacturers sometimes compress chips with binding straps or in briquette form. Upon arrival, the blocks are easily rehydrated. From a logistics standpoint, coir is non-hazardous and shelf-stable, so it can be stored and transported without special conditions.

Packaging: Bulk cocopeat may come in wrapped pallets of blocks or in large “big bales” (For example, a 25 kg compressed bale of coco husk chips typically expands to around 0.2 cubic meters when loosened). Coco chips can be in smaller bricks or large compressed bales as well. The ease of transport extends to on-farm handling: the compact packages can be moved with minimal equipment. One person can carry a 5 kg brick to a tank for hydration, versus multiple people needed to haul equivalent loose media. Overall, transport and storage are very convenient – a clear advantage of both cocopeat and chips. This is one reason they have good shelf presence in retail (small bricks for home gardeners are sold in many garden centers due to portability). It’s worth noting that because coir is shipped globally, there is an environmental transport cost (fossil fuels used in shipping), but many accept this given the renewable nature of coir vs peat.

Compressed cocopeat bricks are one of the most common formats used for easy transport and long-term storage.

Each 5 kg brick (shown dry, before expansion) can yield a wheelbarrow-full of cocopeat once rehydrated. Coco husk chips are commonly packaged in compressed blocks or large bales, making them ideal for bulk handling, storage, and transportation.

Shelf Life and Storage: Both cocopeat and coco chips have an excellent shelf life when kept dry. As essentially inert organic fiber, dry coir does not rot or spoil in storage – it can last for years on the shelf without losing quality. This is a big plus for both retailers and growers: one can buy coir in bulk and store the unused portion indefinitely if it’s kept dry and covered (to avoid contamination). The only issues to avoid are moisture (which could lead to mold growth or partial decomposition over a long time) and potential cross-contamination (keep coir away from fertilizer spills, soil-borne diseases, etc., in storage). Many suppliers age and buffer coir before packaging; aged coir is even more stable and often has reduced phenolic content (raw fresh coir can have tannins that inhibit plant growth, but proper aging/composting for several months removes this concern). By the time it’s pressed into a brick, cocopeat is usually aged and has turned into a stable brown fiber that won’t significantly change during storage. Coco chips, if they were not fully dried, could theoretically develop some mold in the bag – but reputable suppliers will dry and treat them to prevent this. Some growers rinse and dry their coco chips in the sun again upon receipt as a precaution and to remove any slight fermentation smell from packaging. In bulk storage (like a warehouse), it’s best to keep coir pallets off the ground and wrapped – but generally, coir storage is trouble-free compared to something like raw wood chips or compost, which could decompose or attract pests. Rodents or insects are not drawn to dry coir as it has little nutritional value and often contains tannins that deter pests. Shelf life after hydration: Once coir is expanded and wet, its clock for use starts – wet coir, if left piled, can start decomposing or grow fungus. Growers typically use or at least let the coir drain after hydration and do not store it wet for long periods (unless aerated). But one can re-dry coir if needed and reuse it later. In short, dry coco products have an almost unlimited shelf life, while wet cocopeat or chips should be used within a short period unless properly sterilized for long-term storage.

Pricing Comparison: In the market, as of recent years, a single 5 kg cocopeat brick might retail for around $10–$20 (expanding to ~2–2.5 cubic feet of media), whereas a similar weight of compressed coco chips might be slightly higher in price (due to lower demand and volume). Bulk pricing for commercial operations is much lower per unit – contracts might secure coir at a few hundred dollars per ton, for example. The price also depends on origin (coir from Sri Lanka vs India might have slight quality or cost differences) and on the grade. Washed, buffered cocopeat (guaranteed low EC) commands a premium. Coco chips graded for orchids (medium size, washed) also can cost more than ungraded landscape husk chips. If comparing to alternatives: peat moss bales often cost slightly less per volume, and pine bark mulch is usually cheaper than coco husk mulch locally (unless one is in a region with no timber industry but access to coconut). However, the cost can be offset by coir’s reusability and its higher water-holding (meaning potentially lower irrigation costs). Also, in commercial greenhouse use, the consistency and disease-free nature of coir can save money by reducing crop losses and the need for lime (since coir is pH-neutral). Transport costs for coir might be a bit higher because it’s shipped from afar, but the compression mitigates a lot of that – the A-Z Animals analysis notes that shipping time and cost is one reason coir can be pricier than peat in some locales. However, with coir now available from multiple sources, competition has made it quite affordable. Additionally, products like cocopeat grow bags/slabs (ready to hydrate in a sleeve) are sold for commercial use in a very cost-effective way, often cheaper than buying peat and perlite and mixing your own substrate. Coco chips for mulch are a newer product in landscaping, so they tend to be sold in smaller bags at garden centers at a premium (often marketed as “coconut mulch”). For large scale mulching, if sourced directly in bulk, the cost might be comparable to other organic mulches, especially considering it doesn’t need to be replaced as often.

Sourcing Considerations: Buyers should ensure they get coir from reputable suppliers to get consistent quality. Check if the cocopeat/chips are washed (low EC), and what the particle size is. Reputable sources will list the pH (usually ~6), EC, and perhaps CEC of the product. Many university agricultural extensions now have guidelines for using coir and sometimes maintain lists of suppliers or quality parameters to look for. Given coir is a byproduct, sourcing is generally stable (it’s not at risk of depletion like peat bogs), but occasionally logistics (shipping constraints, pandemic disruptions) can cause short-term shortages. Having multiple suppliers or ordering well in advance is wise for commercial users.

Shelf Life during Storage: We touched on shelf life, but to emphasize: both cocopeat and coco chips can be stored for long periods as long as they are dry. For example, a grower could purchase a year’s worth of coco blocks and stockpile them without worry of degradation. This is a big advantage over something like rice hulls or certain compost-based media that can’t be stored that long. Even once opened, the unused dry coir can be kept in a bin. This flexibility in sourcing (buy in bulk, store dry) allows growers to take advantage of off-season pricing or bulk discounts, knowing the product won’t spoil.

In conclusion, cocopeat and coco chips are comparably easy to source, ship, and store in bulk. Cocopeat is ubiquitous in the horticultural supply chain now, and coco chips, while more specialized, are also obtainable for those who need them. Both offer long shelf life and come compressed for economical transport. Price-wise, coir products may entail a higher initial cost than some traditional media, but their benefits and reusability often justify the investment for both small-scale and commercial growers who prioritize sustainable and effective growing substrates.